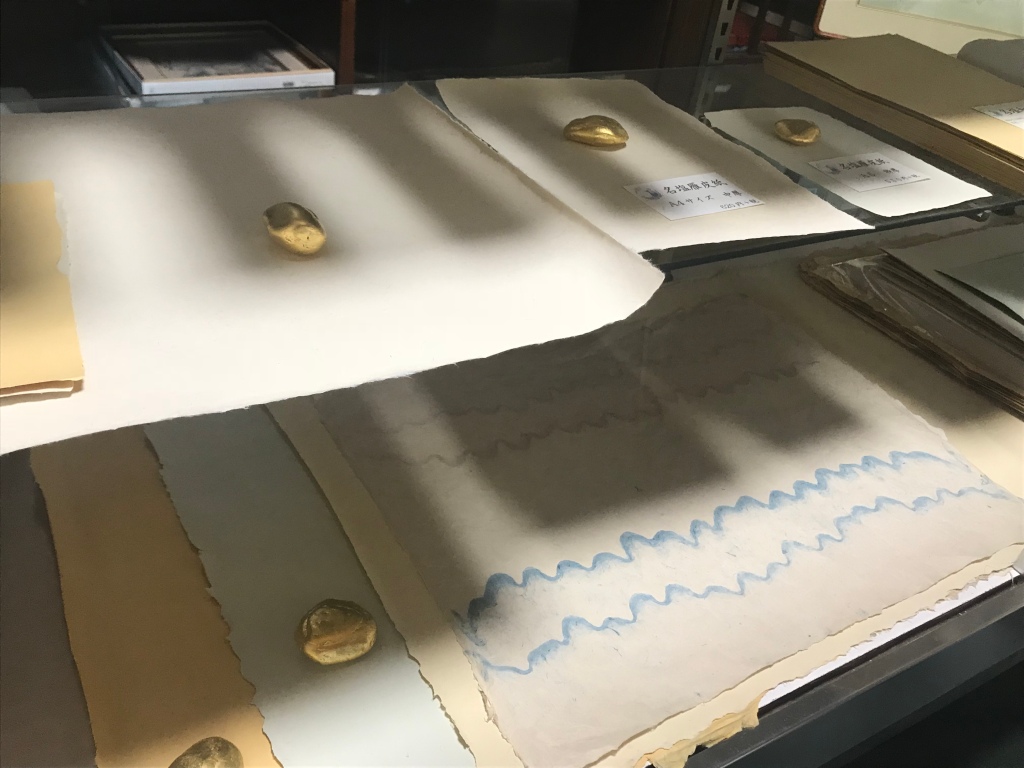

While in Japan, I was fortunate to take a tour to Nishinomiya-Najio in Hyogo Prefecture, Japan in 2018 with the Community House Information Center in Kobe to witness traditional Japanese washi-making at Tanitoku Seishisyo, the studio of Tanina Takenobu, who specializes in making Najio-Gampi-shi washi. Takenobu Tanino was designated as a living national treasure in 2002 and passed the artisanship on to his son, Masanabu Tanina, who gave us a demonstration of the process, which uses mud to make the washi paper robust, prevent color fading and repel insects. The paper is used in Important Cultural Properties including Nijo Castle, Nishi Hongan-ji, Katsura Imperial Villa and other Imperial villas in Nikko and Numazu. Today, their paper is indispensable for the restoration of National Treasures of Japan.

As a poet and writer I’ve been obsessed with papermaking and bookmaking for years. I love how these arts are integrated into Japanese spirituality, as I discovered with shodo, Japanese calligraphy. I made my first handmade book when I was in the fourth grade and never stopped. I even taught my kids to make paper when they were 4-years old; and taught papermaking, bookmaking and storytelling at their Montessori school.

People often used to ask me, why on earth would I make paper? Or bread, or grow your own tomatoes, when you can just buy it in the store? The Brother’s Grimm fairy tale of The Handless Maiden explains that machines sacrifice something in us if we don’t do it ourselves manually. Handmade paper always reminds me of the value of handmade items beyond a monetary unit in a system designed around values of efficiency rather than contemplation.

As the root word of machine comes from the Greek meaning trick. Machines and technology are amazing, yet they can isolate, alienate and dehumanize. Slow-food and artisan culture preserve the humanities for civilization to flourish and survive the machine that has been commodifying our lives by flattening out and destroying our normally deep relationship to nature that the Japanese revere so much.

Gampi is a slow-growing bush from the Wikstroemia family that provides the raw material for making 雁皮紙 Gampi-shi washi paper. It can’t be cultivated so must be collected in the wild. Mud is collected and filtered in a cotton bag. Only filtered fine mud is used for making paper, whose color depends on the shade of mud. Mud usually sinks in water. However, the mountain water of Najio helps mix pulp and water evenly. In Najio, papermaking began in the Muramachi period, and by the middle of the Edo period, small paper mills in the area numbered 1,000, which is where Najio gets its name, najio senken literally means meaning a thousand workshops in Najio.

While Kouzo papers made from mulberry were introduced from China, Gampi papers originated in Japan. Moreover, Najio-shi draws attention for its unexceptional, unique and oldest papermaking method called tamesuki, which was not introduced in other parts of Japan. The artisan process is remarkable, taking pain-staking tedious and time-consuming work that produces something of extraordinary value in a world made over in globalist hegemony of consumerism and mass-production that came to Japan post World War II.

Great post! Interestingly, this reminded me of an article I read years ago about Japanese denim. The same dedication and tediousness in producing Japanese denim is also present in this washi-making process you wrote about, resulting in an item that fulfills both function and aesthetics.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey, thanks! And that’s great to know about Japanese denim. More wonderful things to know about Japanese culture. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person